What is casual significance?

Exemplary Work, Interactive Design, Music,

8/3/07

Casual significance is when easy-to-read things point to hard-to-grasp things. Like the taste visualization in Ratatouille. Or Different Trains. Or the color organ in Close Encounters of the Third Kind. They take a stab in the dark, doing things you’d like to build theories around but shouldn’t, and as such they enable you to walk into the unknown with joy and confidence.

I admire Steve Reich’s Different Trains as much as any piece of music written in the latter half of the 20th century because it speaks in a unique language that’s totally specific to its content and yet whose fluency is easy to adopt and understand. Even though it contains constant abrupt shifts in tempo and harmony, even though it takes a programmatic stance on the connection between speech and melody, even though it references the Holocaust, it succeeds in doing all of these things simultaneously while remaining highly accessible to the untrained ear.

My kids have heard the first, joyful movement of Different Trains, and they love it. They enjoy the voices, the repetition, the rhythms, the sound effects, even though it’s like no other piece of music they’ve ever heard. They haven’t been exposed to the subsequent movements yet, and they have no concept of the overall theme of the work, but it’ll be waiting for them when they’re ready, and what will pull them towards it is simply the way in which the work’s strategies unfold in time. That’s casual significance.

So what would casual significance look like in the interactive arena? We’re quickly becoming surrounded by the casual; EA recently stated that they see the casual market as the biggest opportunity in gaming. Most of these games are fun diversions and nothing more, which is fine. The burgeoning “serious games” market is definitely a kind of casual significance, but significance in that context is usually defined solely as social responsibility. I wholly support the growth of serious games, but that’s not really what I’m talking about here.

No, when I talk about casual significance I’m talking about easy-to-read interactive experiences that point to the mysteries of the human condition. Those mysteries might be sensual, or spiritual, or philosophical, and the goal of the experience is not to teach a class about them, but simply to point to them. I love how visual music and synaesthetic works tend to put you in this space instantly and almost effortlessly.

Shining Flower, the CD-ROM I profiled last week, is probably my favorite existing example of this in the interactive realm (though its actual interactivity is meager), as it nails the M.O. of casual significance—simple things pointing to deeper things. Fumito Ueda’s Ico and Shadow of the Colossus come close, but as much as I admire them I think their game mechanics are too prominent to truly classify them as “casual” experiences.

Works of casual significance are high on aesthetics and groove, low on guilt and training, and they index hidden depths. They’re what I wish I was playing when I play the Wii.

The Wiimote and transitional space

Interactive Design, Wii,

7/31/07

Wired recently featured a piece about new work being done using the Wiimote as an interface for real-world training simulators running in Second Life. Surgery, hazardous chemical handling, nuclear plant operations—all are fair game for WorldWired, a consultancy run by David E. Stone, who calls the Wiimote “one of the most significant technology breakthroughs in the history of computer science.”

Well, obviously I think the Wiimote’s pretty nifty too, but it’s only partly for the reasons given by MIT professor Eric Klopfer in the article: “People know intuitively what to do with it when they pick it up because we use it like devices we are familiar with—bats, rackets, wands, etc.”

So much Wiimote boosterism is about where the remote takes you—the mental models it so seamlessly helps you to adopt. All true, but I would argue that of equal significance is what the remote helps you leave behind. Imagine that the Wiimote comes into widespread usage as an alternative PC input device. Not something you use every day, but something you keep next to your work machine, since you can use it as a PowerPoint or iTunes remote, as well as for those all-too-rare moments when you stumble across a Flash game, online comic or art piece that shows you the delightful message: “If you have a Wiimote, pick it up now.”

Instantly, you’ve left behind the world of work and its input devices, and you’re prepared to experience something unusual—the more unexpected, the better. Even if the piece doesn’t make use of the remote’s motion sensitivity at all, the device itself has still managed to carve out headspace where software art and entertainment no longer have to compete with every other application to remap the meanings of your mouse and keyboard. We’ve got transitional space now; we’ve got a lobby to ease people out of the workaday and into alternate realms.

Calling it a technological breakthrough just doesn’t do it justice, does it?

Shining Flower: an appreciation

Exemplary Work,

7/27/07

Pictured at right: the cover of one of my all-time favorite digital experiences, the almost completely non-interactive Shining Flower (aka Hikaru Hana), developed by Maze Inc. and published by The Voyager Company, with concept and illustrations by Kikuko Iwano. My niece (those are her cornrows you see at the bottom of every page) recently returned to me the Power Macintosh 8500/120 I lent her when she went to college, and with it I regained the ability to run Shining Flower, to my delight.

Shining Flower was published in 1993 while I was working at Voyager as an audio commentary editor for the Criterion Collection. I have vague memories of seeing it demoed at one of the monthly open houses Voyager held at their offices on the beach at Santa Monica. Love at first sight; that immediate feeling of creative jealousy you get when you see something you wish you’d made. I bought it.

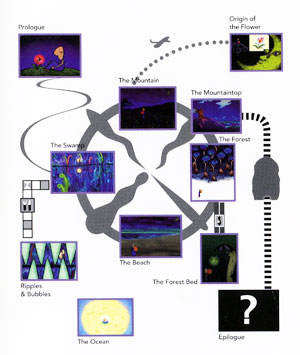

Shining Flower is beautiful, contemplative, quiet, and makes excellent use of limited resources. It’s not pretending to be a movie, or cel animation, or anything other than an 8-bit Director piece (with exemplary use of the lost art of color cycling, I might add). A single character holding a glowing flower makes his/her way through a series of surreal vignettes, on a kind of spiritual journey. Interactivity is limited to basically choosing which several-minute-long sequence you want to watch next.

I remember some grumbling at Voyager about the lack of interaction; at a company which was pioneering the application of same to content of cultural significance, why publish this? On the surface, it did appear to be a misstep, but if you caught the spirit behind this piece—the total commitment to expressing something in this medium, approaching it with the same respect afforded to cinema or literature, fully embracing the technology of the day without harboring self-defeating disdain for its limitations—the appeal of the work was undeniable.

Now when I watch it I find myself wanting to write code that makes it all dynamic, semantic, syntactic and syllabic…

Enjoy: the “beach” vignette of Shining Flower.

Recent Posts

Go InSight: Composing a Musical Summation of Every Mission to Mars (Part 2)

Making music out of the data of interplanetary exploration.

Go InSight: Composing a musical summation of every mission to Mars (Part 1)

Making music out of the data of interplanetary exploration.

Cited Works from “Storytelling in the Age of Divided Screens”

Here’s a list of links to works cited in my recent talk “Storytelling in the Age of Divided Screens” at Gallaudet University.

Timeframing: The Art of Comics on Screens

I’m very happy to announce the launch of “Timeframing: The Art of Comics on Screens,” a new website that explores what comics have to teach us about creative communication in the age of screen media.

The prototype that led to Upgrade Soul

To celebrate the launch of Upgrade Soul, here’s a screen shot of an eleven year old prototype I made that sets artwork from Will Eisner’s “The Treasure of Avenue ‘C’” (a story from New York: The Big City) in two dynamically resizable panels.

Categories

Algorithms

Animation

Announcements

Authoring Tools

Comics

Digital Humanities

Electronic Literature

Events

Experiments

Exemplary Work

Flash

Flex

Fun

Games

Graphic Design

Interactive Design

iPhone

jQuery

LA Flash

Miscellaneous

Music

Opertoon

Remembrances

Source Code

Typography

User Experience

Viewfinder

Wii

Archives

July 2018

May 2018

February 2015

October 2014

October 2012

February 2012

January 2012

January 2011

April 2010

March 2010

October 2009

February 2009

January 2009

December 2008

September 2008

July 2008

June 2008

April 2008

March 2008

February 2008

January 2008

November 2007

October 2007

September 2007

August 2007

July 2007

June 2007